The Leadership Pipeline model - Claus Elmholdt has worked for 15 years with research and development in learning, management and organizational psychology, partly as a researcher at Aarhus University and Aalborg University and partly as a partner in the consultancy firm Udviklingskonsulenterne and now LEAD - enter next level. Current research interests are Leadership Pipeline, boundary-crossing leadership, leadership team development and distributed leadership processes in teams. He is currently working on the book "ledelsespsykologi", which will be published in the fall of 2013, and has most recently published the anthology "følelser i ledelse" (2011).

The Leadership Pipeline is one of the most influential theories on leadership and talent development in the last decade (Kaiser, 2011). The theory assumes that successful leadership depends on what needs to be led and that the leadership task is different at different levels of the organizational hierarchy (Charan, Drotter and Noel, 2001; Goldsmith and Reiter, 2007; Freedman, 1998).

The theory became widespread with practice-oriented books such as The Leadership Pipeline (Charan, Drotter and Noel, 2001) and What Got You Here Won't Get You There (Goldsmith and Reiter, 2007), both of which focus on identifying and describing the different skills, priorities and values required at different levels of leadership. A third book worth mentioning in this context is Freedman's (1998) Pathways and Crossroad's, which takes a more psychological focus and thematizes the transitions between organizational leadership levels as a triple challenge of learning, unlearning and retaining the right competencies to succeed at a new leadership level. Kaiser (2011) points out that the research base underpinning the theory as presented in these books is thin. For example, the two international bestselling books 'The Leadership Pipeline' and 'What Got You Here Won't Get You There' do not refer to a single empirical study or formal underlying theory. In a Danish context, interest in the Leadership Pipeline has escalated in the last two years, with several practice-oriented articles being published (Moritsen, 2011; Sparre and Moritsen, 2011; Elmholdt 2012a). Particularly in the public sector, where an adapted version of the Leadership Pipeline competency model has been research-based described and disseminated by Thorkil Molly Søholm and Kristian Dahl (Dahl and Søholm, 2012).

This article examines the empirical basis for the Leadership Pipeline. First, the Leadership Pipeline model of leadership trajectories and crossroads in upward transitions between organizational leadership levels is described (Freedman, 1998; Charan, Drotter and Noel, 2001). It then focuses on the central question: Are the competencies of successful leadership really systematically and significantly different at different organizational leadership levels? General research literature on changing job content and role demands at different levels of management is reviewed, and recent research on the relationship between continuity and discontinuity in leadership competencies across organizational levels is presented and discussed. Finally, the limitations of a competency-based approach to the Leadership Pipeline model are discussed and it is suggested that successful leadership depends equally on the leader's ability to demonstrate dynamic situational flexibility in the leadership role at the current level of leadership.

Read more about our training

LEAD offers certification in the development of agile leadership with the development tool "Leader Versatility Index" (LVI)

With a certification, you will be equipped to use LVI in development processes in your organization at the individual, group and organizational level.

Leadership pipeline model - Leadership trajectories and crossroads in upward transitions

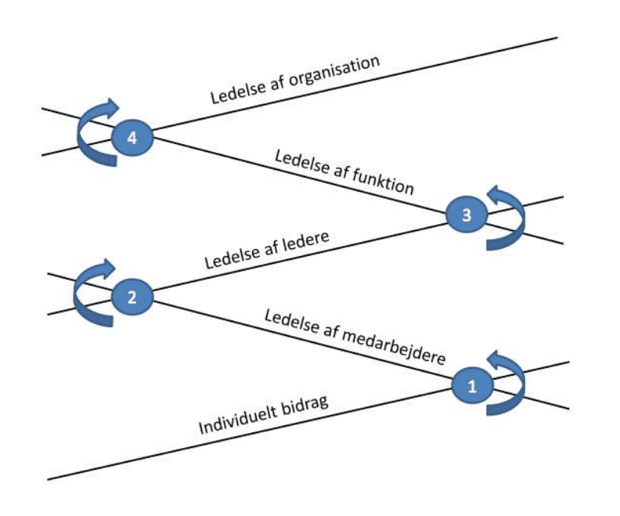

Charan, Drotter and Noel (2001) describe a Leadership Pipeline model with six leadership levels and corresponding transitions, which is well suited to large multinational companies. Other authors work with three (Kaiser and Craig, 2011) or four levels of leadership (Freedman, 2011), which is better suited to smaller companies, which is prevalent in the Danish context. It is a separate point in the Leadership Pipeline literature that the generic typology described below with four levels must be adapted and unfolded specifically into the local organizational context.

Passage 1: From individual contributor to leader of employees. The movement from individual contributor to leader of employees is the first transition in the Leadership Pipeline model. The employee role is characterized by creating success through one's own contribution, which draws on disciplined professional competencies. Recruitment to the manager role is typically based on good performance in the employee role - good quality on time, commitment and good collaboration skills - which presents a paradox in Leadership Pipeline thinking that highlights the significant differences between the roles of individual contributor and manager of employees. The challenge in this passage is described as one of skill, prioritization, and not least an emotional shift "...from "doing" work to getting the work done through others" (Charan, Drotter and Noel, 2001, p. 17).

Passage 2: From managing employees to managing managers. Perhaps the biggest difference is that you now become a full-time manager. This means that the leader must take a more holistic strategic perspective on the business, which in turn means that it is essential that the leader at this level has undergone a value integration with the leadership role - i.e. understands, experiences and identifies themselves as a leader. On the prioritization side, it's about letting go of operations and spending time on strategic work and coaching your own leaders. Charan, Drotter and Noel (2001) emphasize coaching as a key competence of managers for managers, because they have a great responsibility for the development of first line managers. It's about having the courage and vision to promote employees who have the right potential to become leaders, and here it becomes crucial that the manager's own values, skills and priorities are firmly rooted in the leadership role:

Managers at passage two need to be able to identify value-based resistance to managerial work, which is a common reaction among first--line managers. They need to recognize that the software designer who would rather design software than manage others cannot be allowed to move up to leadership work (Charan, Drotter and Noel, 2001, p. 19).

Managers of managers must also have the courage to help managers of employees who are unable to develop joy and emotional engagement in their leadership role over time, back into an employee role.

Passage 3: From managers of managers to functional leader. The task at this level is to create results through a complex function. For example, the head of social services in a municipality who manages a complex area of responsibility where a number of different specialist areas must be coordinated and interconnected to create the best possible resource utilization and quality for the citizen. The functional manager must be able to mediate between different interests and perspectives with relative ease - not be torn apart by conflicting viewpoints, but be able to integrate functional strategies with the overarching business or political strategy. This requires good leadership maturity, i.e. perspective awareness and the ability to understand and regulate one's own and others' emotional behavior in a strategic context. Furthermore, this level requires that the leader is able to work with future-oriented thinking and a long-term perspective without losing insistent momentum in daily life.

Passage 4: From functional manager to top manager. Moving through the fourth passage is more about values and mindset than skills. In this transition, the functional leader must reinvent themselves as a top leader who drives results through an organization. The top leader must engage in long-term visionary thinking without losing focus on the ongoing optimization of business efficiency and profitability. At this level, the leader must finally let go of 'darlings' - products or customers that have received special attention - and take responsibility for the whole. In particular, it is about developing priorities and values that provide the basis for a holistic view of the business, which implies a subtle shift from strategic thinking to visionary and global thinking (Charan, Drotter and Noel, 2001, p. 26).

Public management

LEAD helps public organizations create increased value for citizens and society by strengthening their leadership.

We collaborate with KL and the Crown Prince Frederik Center for Public Management on knowledge and method development. In recent years, we have been the supplier for the majority of the interdisciplinary management training in the Danish state and have been a trusted advisor for several of the major strategic management challenges in the municipalities and regions.

Does it take different skills to succeed at different levels of management?

There is no direct empirical test of the central Leadership Pipeline hypothesis; that different competencies are required to succeed at different levels of leadership (Yukl, 2009), but there is a substantial body of research-based literature describing job content and role requirements as different in different leadership positions (Dai and De Meuse, 2013). One of the early examples is Hemphill's (1959) identification of ten dimensions of the managerial role, which were found to be of varying importance at different levels of management and in different managerial functions. Hemphill's research can be seen as an early exponent of what has later been called the continuity perspective on leadership (De Meuse, Dai and Wu, 2011). This research highlights that the competencies of effective leadership are the same across leadership levels, but that the importance and demands of competency levels increase with upward transitions. In contrast, the discontinuity perspective, as exemplified in the Leadership Pipeline model (Charan, Drotter and Noel, 2001), highlights that the leadership competencies of effective leadership at lower levels of management can be directly negatively related to success at higher levels, and that leaders in upward transitions must therefore let go of some skills, priorities and values and acquire others. The concept of competence refers to practical ability, and is used here as an umbrella term for skills, priorities and values.

Another example of research identifying differences in job content and role requirements is Mintzberg's (1975) description of ten essential leadership roles: top figure, leader, connector, monitor, information distributor, spokesperson, entrepreneur, crisis solver, resource distributor and negotiator. The roles are divided into three clusters: (1) interpersonal roles, (2) information roles and (3) decision-making roles. Although Mintzberg did not directly address the question of whether different competencies are required to succeed at different levels of management, he did observe that the amount of time managers spend on different management roles varies across hierarchical levels of management (Ibid.).

In a recent review of the existing research-based literature related to the Leadership Pipeline, Kaiser, Craig, Oversfield and Yarborough (2011) conclude that job content and role requirements at different levels of management vary on dimensions such as time horizon, complexity, functional activities and scope of organizational responsibility. Thus, there seems to be evidence that job content and role requirements differ at different levels of management, which is an important foundation for validating the Leadership Pipeline model. However, there is a great need for new research that focuses directly on empirical testing of the validity of the Leadership Pipeline model. In recent years, several studies have been conducted with this aim, of which I will highlight three in the following. De Meuse, Dai and Wu (2011) examined the issue of continuity and discontinuity in upward leadership transitions through an analysis of 360-degree leadership evaluations. The study included an analysis of the rated importance of 67 leadership competencies across leadership levels as well as an analysis of leaders' achieved scores. The analysis showed that the reported importance of leadership competencies increases at higher levels of management for all but one competency, professional technical knowledge, whose reported importance decreases. This finding supports a continuity perspective. The analysis of managers' scores on the 360-degree assessment showed that for 44 out of the 67 competencies, there were no significant differences in the average score across hierarchical management levels. On 13 competency dimensions, higher-level managers scored significantly higher, and on 10 competency dimensions, lower-level managers scored significantly higher. This finding supports a discontinuity perspective. In other words, managers appear to let go of some competencies and acquire others as they move upward through the job.

For example, it seems that middle managers in particular need to focus on developing their interpersonal management skills in order to succeed, while the transition to the managerial level is associated with the development of strategic business skills. At the same time, managers seem to let go of their interpersonal management competencies to some extent, at least De Meuse, Dai and Wu (Ibid.) find that top managers achieve lower scores on interpersonal management competencies than middle managers. An interesting point in this regard is that, as De Meuse, Dai and Wu point out, arrogance and insensitivity in interpersonal matters are some of the main reasons why top managers leave their jobs (Hogan, Hogan and Kaiser, 2010). Overall, the findings suggest that both continuity and discontinuity are at stake for leaders in upward transitions and that the ability to flexibly let go, retain and build on therefore becomes a key meta-competency.

In a study of the relationship between leadership competencies and leadership effectiveness, based on data from 2,175 managers at different levels of management, Kaiser and Craig (2011) found support for the discontinuity thesis. They observed that the competencies of effective leadership shifted across leadership levels and that these shifts were in most cases discontinuous, such that a competency that correlates positively with leadership effectiveness at one leadership level can be transformed into a negative predictor of leadership effectiveness when moving to another leadership level. For example, they found that empowerment was not a statistically significant predictor of first-line managers' effectiveness, while it was a negative predictor of middle managers' effectiveness, but a positive predictor of top managers' effectiveness. The only one of seven leadership competencies examined that was positively related to successful leadership at all hierarchical levels of management was learning agility (Ibid.). One possible interpretation of these results is that learning agility is a key generic competency that increases the likelihood of successful upward leadership transitions. Learning agility can be defined as: "the willingness and ability to learn from experience, and subsequently apply that learning to perform successfully under new or first-time conditions" (De Meuse, Dai and Hallenback 2010, p. 120). The concept of learning agility is not specifically related to vertical transitions, but is a general expression of leaders' ability to learn and to flexibly adapt to changing conditions and challenges. De Meuse, Dai and Hallenback (2011, p. 127) conclude that it is obvious that learning agility could be used as an early indicator of an individual's potential for successful upward leadership transitions. A practical implication of this, if future research further validates these findings, is that a valid test of learning agility could usefully supplement or even replace general personality-based recruitment tools.

Mumford, Champion and Morgeson (2007) are based on an operationalization of leadership as stratified (strata) and segmented (plex) into four competency categories: (1) cognitive competencies, (2) interpersonal competencies, (3) business competencies and (4) strategic competencies. They test the model on a sample of 1000 team leaders, middle managers and senior managers. Their findings support that the four categories of leadership competencies are relevant in any leadership job, but that leadership jobs at higher organizational levels require a higher level of competency in all areas (continuity). Furthermore, in support of the discontinuity perspective, they find that unlike cognitive competencies, which are important at all organizational levels, strategic competencies only really become important at the top management level. In summary, the preliminary research supports the Leadership Pipeline assumption that the competencies behind successful leadership depend on the leadership task and that this differs at different hierarchical levels of leadership. In addition, the results of the studies suggest that there is both continuity and discontinuity at stake for leaders in upward transitions. A weakness of all three studies is that they were not developed specifically based on the Leadership Pipeline theory and therefore cannot be used as a direct empirical test of the model. Furthermore, there is a need for more long-term studies that follow leaders in transition over time, in addition to cross-sectional studies.

Discussion - the limitations of the competency approach and the need for flexible management

The above literature review reveals that almost all research related to the Leadership Pipeline takes a competency approach that focuses on examining which specific competencies are linked to effective leadership at different levels of management. The practical implication of this, as operationalized in the Leadership Pipeline model, is that leaders in upward job transitions are assumed to need to acquire some specific competencies and let go of other specific competencies in order to make the transition successfully. At the same time, several leadership researchers point out that specific competencies are not determinants of effective leadership, but rather combinations of competencies (Zaccaro, 2007; Dai and De Meuse, 2013) and the ability to demonstrate dynamic situational flexibility in the leadership role (Yukl and Lepsinger, 2004; Mintzberg, 2010) that are crucial for leadership effectiveness.

The Leadership Pipeline theory focuses on the leader's flexibility (learning agility) in connection with vertical transitions between management levels, while the literature on flexible leadership equally highlights what could be called horizontal flexibility (Yukl and Lepsinger, 2004; Kaiser and Overfield, 2010). It is not only in the context of vertical transitions that flexibility is needed. Conflicting organizational needs such as innovation vs. efficiency and relationships vs. results are eternal dilemmas that cannot be solved, but must be managed through flexible situational leadership. Flexible leadership can be defined as the effective adaptation of leadership styles, methods and approaches to changing situations and leadership tasks in order to promote organizational performance (Kaiser and Overfield, 2010 p. 106). This places great demands on the leader's reflexive capabilities and ability to act on the fly. Firstly, the leader must be able to analyze a given situation and assess what managerial action response it calls for, and secondly, the leader must be able to perform the appropriate managerial action effectively (Elmholdt 2012b). Mintzberg describes this as mastering a dynamic balance and at the same time criticizes management programs that build development paths as a collage of competence modules:

It is this dynamic balance that makes teaching leadership techniques in a classroom redundant, especially when it addresses one role or competency at a time. Even mastering all the competencies does not necessarily make for a competent leader, because the key to this work is being able to blend all its aspects in a dynamic balance (Mintzberg, 2010, p. 140).

The Leadership Pipeline model contains a degree of inconsistency in this regard. On the one hand, it is argued that organizations should develop a Leadership Pipeline model to ensure an efficient flow of internal leadership development. Charan, Drotter and Noel (2001) point out that a key management task at all levels is to recruit and develop a food chain of leadership talent. This argument, that leadership development is best undertaken in an intra-organizational context, is consistent with a situated understanding of learning as changed participation in changed social practices (Lave & Wenger, 1991). On the other hand, the Leadership Pipeline model's operationalization of checklists of specific competencies to be learned at each level of leadership is in direct opposition to a situated understanding of learning as the whole person's changed participation in specific leadership practices. Dai and De Meuse (2013, p. 167) point out that future research on the Leadership Pipeline should focus more on longitudinal studies that can uncover interactions and patterns of competencies and how effective leadership emerges and develops in relation to specific contexts. A practical implication of this is that organizations must avoid too narrow a focus in their work with the Leadership Pipeline on descriptions of competency checklists, which in itself does not ensure a coherent leadership chain and the right leadership at the right level. On the contrary, as Dai and De Meuse (Ibid.) point out, a narrow target focus on specific competencies can risk creating blind spots, because effective leadership in many situations is not about specific competencies, but about the ability to balance paradoxes and dilemmas (Quinn, Spreitzer).

Conclusion

The Leadership Pipeline is current leadership fashion, no doubt about it, but how much essence is there beneath the glittering surface? In this chapter, I have examined the empirical basis for the central hypothesis of the Leadership Pipeline; that the competencies behind successful leadership differ at different hierarchical levels of management. In conclusion, the research literature generally supports that job content and role requirements differ at different hierarchical levels of management. In addition, recent studies on the validity of the Leadership Pipeline theory suggest that there is both continuity and discontinuity at play for leaders in upward transitions. Finally, the competency approach to the Leadership Pipeline model was discussed, and it was problematized that a narrow focus on specific competencies risks throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

References

Charan, R., Drotter, S., and Noel, J. (2001) The leadership pipeline: How to build the leadership powered company. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dahl, K. and Molly Søholm, T. (2012) Leadership Pipeline in the public sector. Copenhagen: Danish Psychological Publishing.

Dai, G. and De Meuse, K.P. (2013) Types of leaders across the organizational hierarchy: A personcentered approach. Human Performance, 26, 150--170.

De Meuse, K.P., Dai, G. and Hallenbeck, G.S. (2010) Learning Agility: A construct whose time has come. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, vol. 62, no. 2, 119-130.

De Meuse, K.P., Dai, G. and Wu, J. (2011) Leadership Skills across Organizational Levels: A Closer Examination. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 14, 120-139.

Elmholdt, C. (2011) Authentic leadership in the emotional organization. IN: C. Elmholdt & L. Tanggaard (eds.). Emotions in leadership. Aarhus: Forlaget Klim.

Elmholdt, C. (2012a) Leadership Pipeline - more than just a new buzzword? Copenhagen: Børsens Ledelseshåndbøger, September 2012.

Elmholdt, C. (2012b). Flexible leadership - at the crossroads. Management today, no. 9.

Freedman, A. (1998) Pathways and crossroads to institutional leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal. 50, 131-151.

Freedman, A. (2011) Some Implications of Validation of the Leadership Pipeline Concept: Guidelines for Assisting Managers--in--transition. The Psychologist--Manager Journal, 14, 140--159.

Goldsmith, M., and Reiter, M. (2007) What got you here won't get you there. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Hemphill, J.K. (1959) Job description for executives. Harvard Business Review, 37, 55-67.

Hogan, J., Hogan, R. and Kaiser, R.B. (2010) Management derailment: personality assessment and mitigation. In: S. Zedeck (Ed.). APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, (pp. 555 - 575). Washington DC: APA.

Kaiser R.B. (2011) The Leadership Pipeline: Fad, Fashion, or Empirical Fact? An Introduction to the Special Issue. The Psychologist Manager Journal, 14, 71-75.

Kaiser, R.B. and Overfield, D.V. (2010) Assessing Flexible Leadership as a Mastery of Opposites. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, vol. 62, no. 2, 105-118.

Kaiser, R.B. and Craig, S.B. (2011) Do the Behaviors Related to Managerial Effectiveness Really Change With Organizational Level? An Empirical Test. The Psychologist Manager Journal, 14, 92-119.

Kaiser, R.B., Craig, S.B., Overfield, D.V. and Yarborough, P. (2011) Differences in managerial jobs at the bottom, middle, and top: A review of empirical research. The Psychologist Manager Journal, 14, 76-91.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mintzberg, H. (1975). The Manager's job: Folklore and fact. Harvard Buisness Review, 53, 100-110.

Mintzberg, H. (2010) Mintzberg on leadership. Copenhagen: L&R Business.

Mouritsen, P.K. (2011) Leadership Pipeline - in Danish. Ledelseidag no. 5. Mumford, T.V., Campion, M.A. and Morgeson, F.P. (2007) The leadership skills strataplex: leadership skill requirement across organizational levels. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 154-166.

Sparre, N. and Mouritsen, P.K. (2012) Leadership Pipeline in the public sector. Copenhagen: Børsens Ledelseshåndbøger.

Quinn, R.E., Spreitzer, G.M., and Hart, S.L. (1992) Integrating the extremes: Crucial skills for managerial effectiveness. In: S. Srivastva and R.E. Fry (Eds.). Executive and organizational continuity. San Francisco: JosseyBass.

Yukl, G. (2009) Leadership in organizations (7th Edition). New York: Pearson Education, Prentice Hall. Yukl, G. and Lepsinger, R. (2004) Flexible leadership: A conceptual and empirical analysis of success.

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Zaccaro, S.J. (2007). Trait--based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62, 6-16