Effective interdisciplinary leadership teams can create a leadership space that transforms interfaces and disciplinary boundaries into new productive spaces for collaboration around strengthening the core mission of public schools: The development of children and young people's learning and well-being

Key to strengthening the core task

The school reform has led to a significant need to strengthen cross-disciplinary leadership between teachers, educators and other professionals in schools across the country. However, while there is an increased focus on interdisciplinary leadership teams, there are still doubts about how to make the new interdisciplinary leadership teams work and create good results. Successful interdisciplinary collaboration in schools requires effective leadership teams with an eye for cross-disciplinary leadership and the ability to create common direction, alignment and commitment throughout the organization.

Interdisciplinary leadership teams have enormous potential to strengthen the core task of primary and lower secondary schools - the development of children and young people's learning and well-being. Therefore, interdisciplinary leadership teams must take the lead in making the new and even closer interdisciplinary collaboration work in practice. This work obviously starts with the establishment of effective leadership teams that exercise leadership that supports developing and coherent learning trajectories for children in the new integrated full-day school. But how do you effectively manage the 'spaces in between' between professional groups, departments and management levels so that interfaces and professional boundaries are developed into collaborative spaces around the common core task? And how do you tie the organization together so that former barriers become bridges for coordinating collaboration on common goals and tasks?

From interface to collaboration space

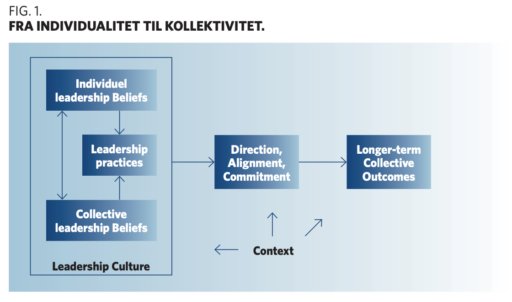

If the new cross-functional leadership teams are to succeed, it requires that disciplinary boundaries and interfaces that were previously responsible for loss of efficiency, lack of coordination and waste of resources are transformed into collaborative spaces for strengthening the common core task. Successfully creating cross-functional collaboration, coordination and cohesion requires cross-functional leadership teams to develop shared Direction, Alignment and Commitment (DAC). DAC is a management thinking that perceives the essence of leadership as producing Direction - a common direction, Alignment - that resources and activities are coordinated and aligned, Commitment - that everyone feels committed to the common direction (Drath et al, 2008), cf. fig. 1. The challenge for the new interdisciplinary leadership teams is to create common DAC, where previously there was often the opposite situation - lack of common direction, alignment and commitment.

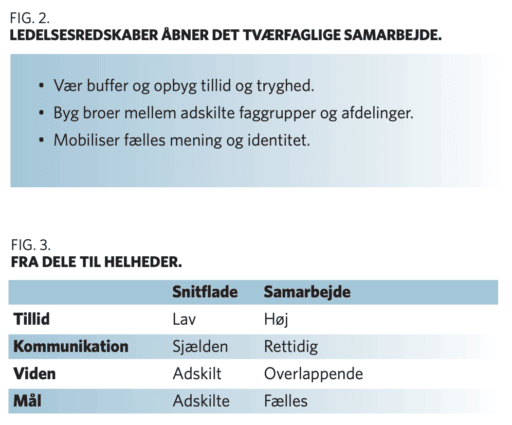

One way to open up interdisciplinary collaboration is to use leadership tools from the research on boundary spanning leadership, which is the art of leading across boundaries - vertical, horizontal, demographic and geographical (Ernst & Chabot-Mason, 2011).

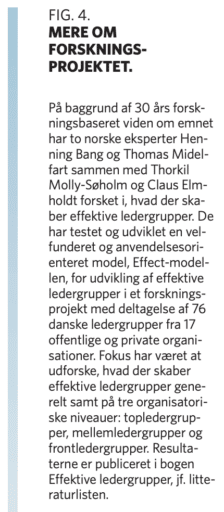

Firstly, the leader of the management team must act as a buffer, establishing safety and trust within the new management team while shielding the group from external danger and threats. Secondly, the leader must try to bridge the gap between the previously separated professional groups and departments, for example, by establishing interdisciplinary meeting structures and practices. Last but not least, the leader must mobilize shared meaning and identity in the interdisciplinary management team by creating meaningful common goals and values that can unite the management team (Ibid.), cf. fig. 2. By creating shared DAC and breaking down previous barriers, the new cross-functional leadership teams can transform former interface-based collaborations into productive collaborative spaces characterized by mutual trust, timely communication, greater knowledge sharing and common goals (Elmholdt & Fogs- gaard, 2014), cf. fig. 3.

Read more about our services for the public sector. Get a tailored program that solves your challenges.

We help public organizations create increased value for citizens and society by strengthening their leadership. We collaborate with KL and the Crown Prince Frederik Center for Public Management on knowledge and method development.

Leadership teams as a prerequisite

One of the most important tasks of the leadership team is to bind the organization together across vertical and horizontal boundaries, ensuring implementation, coordination and collaboration between management levels, departments, disciplines and professional groups. Therefore, effective management teams are obviously one of the keys to success with the increased interdisciplinary collaboration that the new school reform has put at the top of the agenda.

But effective leadership teams don't develop on their own. One of the most common reasons why cross-functional leadership teams fall apart before they even get started is a lack of shared understanding of what the purpose of the leadership team is - what it's set out to produce. Leadership teams without a 'Clear Purpose' lack the basic foundation to ensure common direction, commitment and footing. For the new cross-functional leadership teams to succeed, they must evolve into effective leadership teams, and the first key is the development of a clearly defined shared purpose. The question of how to develop effective leadership teams is one that we at LEAD have explored with two Norwegian leadership experts in a three-year research project involving 76 leadership teams from both private and public organizations, see fig. 4.

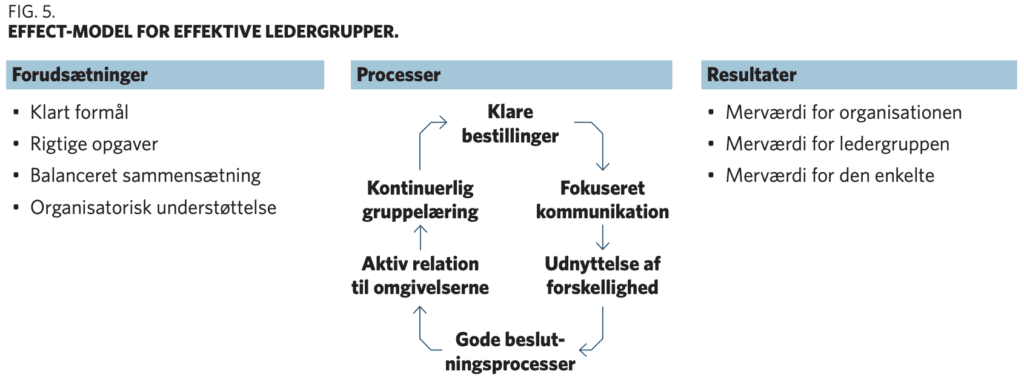

This knowledge about what characterizes effective leadership teams is summarized in the effect model, which is based on the last 30 years of international research on leadership teams. The effect model is structured as a classic input-process-output model with three categories of factors: 1) Assumptions, 2) Processes and 3) Results. The model consists of a number of factors that research has shown to be crucial to the effectiveness of leadership teams, see fig. 5.

The 'prerequisites' category describes some basic conditions that need to be in place for leadership teams to function effectively. Two key factors that leadership teams are often challenged on are 'Clarity of Purpose', which is about whether the leadership team has a clear shared understanding of what the leadership team is set out to create, and 'Right Tasks', which is about whether the leadership team is working on tasks that are aligned with their purpose, require a shared effort and cannot be done as well elsewhere in the organization.

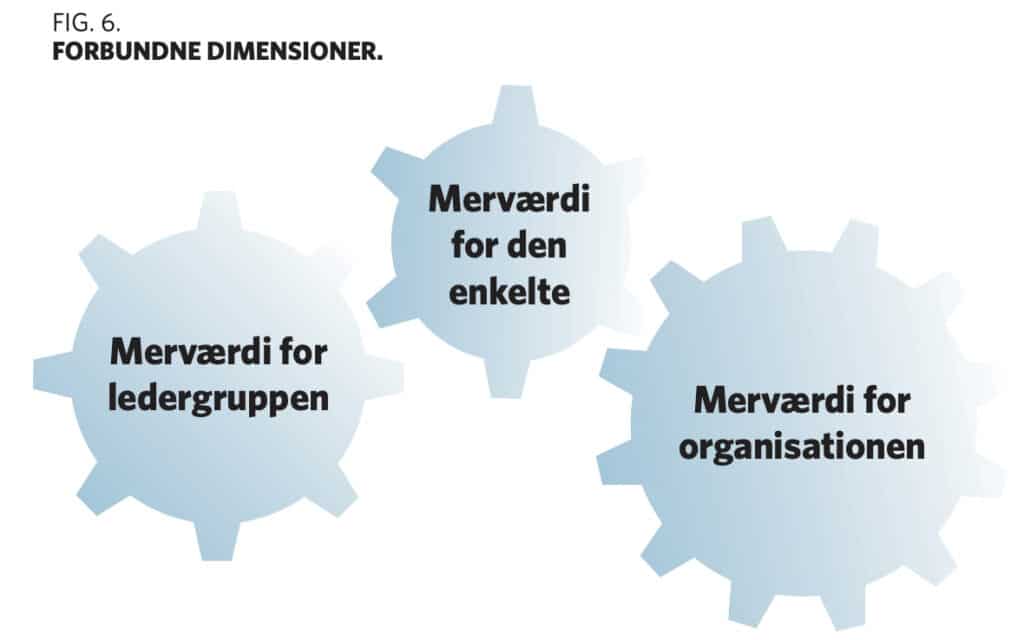

The category 'processes' covers a range of process and collaboration skills and captures the way the management team works together to solve tasks and the relational interaction within the group. Some of the areas that management teams typically struggle to master are 'Focused communication', which is about the ability to stay on point and avoid derailments during management meetings, and 'Continuous group learning', which is about the management team's ability to continuously learn from both its mistakes and successes and regularly evaluate the management team's functioning and performance. The outcome category consists of a number of factors divided into 3 outcome dimensions that mutually influence each other: Added value for the organization, Added value for the leadership team and Added value for the individual (Bang et al, 2015; Molly-Søholm, Elmholdt, Sørensen & Grøn, 2015; Molly-Søholm, Elmholdt, Engelbrecht & Grøn, 2015). A typical challenge in leadership teams is, for example, to convert high Group Psychological Safety and Team Spirit, two factors under added value for the leadership team, into increased added value for the organization.

Many managers rightly perceive 'Added value to the organization' as the most important performance dimension. However, an important point is that the three performance dimensions are closely linked and influence each other. The ability to create added value for the organization is thus closely linked to the ability to create added value for the management team and the individual. Without one, there is no the other, see fig. 6.

This knowledge about what characterizes effective leadership teams is summarized in the effect model, which is based on the last 30 years of international research on leadership teams. The effect model is structured as a classic input-process-output model with three categories of factors: 1) Assumptions, 2) Processes and 3) Results. The model consists of a number of factors that research has shown to be crucial to the effectiveness of leadership teams, see fig. 5.

The 'prerequisites' category describes some basic conditions that need to be in place for leadership teams to function effectively. Two key factors that leadership teams are often challenged on are 'Clarity of Purpose', which is about whether the leadership team has a clear shared understanding of what the leadership team is set out to create, and 'Right Tasks', which is about whether the leadership team is working on tasks that are aligned with their purpose, require a shared effort and cannot be done as well elsewhere in the organization.

The category 'processes' covers a range of process and collaboration skills and captures the way the management team works together to solve tasks and the relational interaction within the group. Some of the areas that management teams typically struggle to master are 'Focused communication', which is about the ability to stay on point and avoid derailments during management meetings, and 'Continuous group learning', which is about the management team's ability to continuously learn from both its mistakes and successes and regularly evaluate the management team's functioning and performance. The outcome category consists of a number of factors divided into 3 outcome dimensions that mutually influence each other: Added value for the organization, Added value for the leadership team and Added value for the individual (Bang et al, 2015; Molly-Søholm, Elmholdt, Sørensen & Grøn, 2015; Molly-Søholm, Elmholdt, Engelbrecht & Grøn, 2015). A typical challenge in leadership teams is, for example, to convert high Group Psychological Safety and Team Spirit, two factors under added value for the leadership team, into increased added value for the organization.

Many managers rightly perceive 'Added value to the organization' as the most important performance dimension. However, an important point is that the three performance dimensions are closely linked and influence each other. The ability to create added value for the organization is thus closely linked to the ability to create added value for the management team and the individual. Without one, there is no the other, see fig. 6.

Leadership teams have potential

In our experience, virtually all forms of inefficiency and loss of efficiency in leadership teams can be eliminated with focused work based on the effect model. Leadership teams always have development potential, but realizing it is even more difficult. It requires both having the right development focus - i.e. working focused on the development areas that create the most value - and doing it in a systematic and persistent way. An obvious way to get started with development work is to use the effect model as a backdrop for reflection and development of your own practice.

From black holes to guiding stars

The new interdisciplinary leadership teams in primary and secondary schools have both productive and destructive potential. They can develop into organizational "guiding stars" that show the way for employees' new and closer interdisciplinary collaboration around the common core task - to strengthen children and young people's learning and well-being. However, there is also a risk that past histories of mistrust, territorial struggles and the pursuit of discipline-specific self-interest can turn interdisciplinary leadership teams into 'black holes' that drain the leadership team and the rest of the organization of energy, efficiency and well-being. Our experience shows that cross-functional leadership teams can become shining organizational beacons, and we hope that our presentation of the research-based effect model and a more detailed description (see fig. 7, following page) will inspire newly established cross-functional leadership teams and help them on their journey towards becoming effective cross-functional leadership teams. It requires a systematic and persistent effort, but if successful, the leadership team can become the powerhouse where the rest of the organization finds inspiration, motivation and direction.

6 tips for cross-functional leadership development

The interdisciplinary leadership teams that have emerged as a result of school reform are both advantaged and challenged. They are advantaged because it is always easier to shape the 'right' foundation for an effective leadership team early on in its creation process, but also particularly challenged because they must succeed with brand new collaborations and increased interdisciplinary coordination at the tail end of a chaotic reform process. As such, the new cross-functional leadership teams have a unique opportunity to shape their own destiny while running the risk of being swallowed up by the external pressures they face. The one thing that is certain is that the new cross-functional leadership teams have the potential to develop into effective leadership teams. But it requires a collaborative effort. Based on the reality that the new interdisciplinary leadership teams must navigate, we see 6 keys that can help open up interdisciplinary collaboration and ensure that the newly established interdisciplinary leadership teams also become effective leadership teams:

1. Create a management culture that produces DAC

It is crucial that leadership teams and managers have a common direction, alignment and commitment (DAC) when leading the way and taking the lead in the organization's development. Therefore, build a culture where it is inevitable that leaders and leadership teams produce DAC both for themselves, but just as importantly, for the rest of the organization. If shared DAC doesn't spread from the leaders and leadership teams to the rest of the organization and its employees, it won't help.

2. Build collaborative spaces on top of interfaces

Use the three leadership tools from boundary spanning leadership research to transform former interfaces and disciplinary barriers into productive interdisciplinary collaboration spaces around the common core task of strengthening children and young people's learning and well-being. Act as a buffer, build bridges and mobilize shared meaning so that the new interdisciplinary collaboration is characterized by mutual trust, timely communication, greater knowledge sharing and common goals. Practice: Establish interdisciplinary meeting structures and forums where the different professional groups can build trust, share knowledge and experience a sense of common purpose.

3. Create a clear purpose

Although it sounds obvious, our experience and research shows that many leadership teams' efficiency losses, irritations, internal tensions and lack of results are due to the fact that they don't have a clear, shared understanding of what their leadership team should produce together. Without a common direction that is anchored in the core task, it's hard to reach the finish line together! Especially new leadership teams often need to create a shared understanding of what their purpose is, which is a good place to start establishing a new leadership team. However, just because your leadership team is older doesn't guarantee that you have a clear common purpose. On the contrary, it sometimes means that the purpose becomes so well understood that you don't realize how much you disagree until it's too late.

4. Work on the right tasks

Are you working on the right tasks in your leadership team? It may seem like a misplaced question, but both research and our practical experience shows that many management teams spend a lot of their time on tasks that don't really belong in the management team. These are typically tasks that are not in line with the purpose of the leadership team, don't require a joint effort or can be better solved elsewhere in the organization. Practice: Discuss in the management team which tasks should belong in the management team and which can and should be solved elsewhere. Typically, such a reflection results in the following realizations: A) that a large part of the tasks you spend time solving in the management team do not belong here at all, but are heirlooms from previous organizations, managers or the like, B) that you spend part of your time solving tasks that can and should be delegated to other people and forums.

5. Align the management team's leadership space and responsibilities upwards, outwards, downwards and sideways

In order to develop an effective management team, it is necessary to clarify your management space and responsibilities. It may seem banal, but what's the point of rushing off and creating results if they're not the results that the management level above you (the management team in the administration), outwards (the school board), downwards (the employees), and sideways (subordinate school management teams) think you should create? Not very much! It is therefore crucial to align expectations with the management level above and stakeholders about the role, responsibilities and tasks of the management team.

6. Create a management team with team qualities

Creating leadership teams with team qualities starts with the realization that leadership team members are straddled between three different types of tasks:

Management team tasks - tasks where the management team has a common goal and is completely dependent on everyone's skills and efforts to succeed.

Interdependent tasks - tasks where one or more members of the leadership team depend on each other to achieve shared or personal goals.

Individual tasks - tasks where the individual manager is not dependent on others and has full responsibility for success.

With this insight comes the realization that leadership groups are not teams in all respects, but that what you should strive for is to develop leadership groups with team qualities. Leadership teams need to be able to operate both as a group and as a team, and pretending to be a team in all respects has negative consequences if it's not grounded in reality, and it rarely is.