Stricter requirements for future leaders

Future leaders are at a crossroads. As the labor market has transformed into a hypermodern society, the work environment has changed significantly (Stacey, 2012). New organizational and business fundamentals have been created. Conditions that are inevitable for both leaders in private and public organizations, and that both actors on the national and international stage must relate to. What future leaders have in common is that they face increased complexity, uncertainty and speed of change in their working lives (Smith & Lewis, 2011, p. 382). The work environment is no longer fixed and continuous, and the speed at which conditions change is an indisputable game changer. Unpredictable customer demand can change the competitive parameters in a split second, and yesterday's competitors can be tomorrow's partners. Future leaders are therefore faced with a key question; how can I succeed and thrive in and under the new world of leadership? This article is aimed at managers and consultants who are interested in this very question

The VUCA world calls for new management tools

The new pace, flexible structures and unpredictable challenges of the workplace can be encapsulated in the American acronym VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity) (Sørensen & Kaiser, 2017; Sørensen & Grøn, 2015). The term VUCA was introduced by the US military in the aftermath of the Cold War (Kinsinger & Walch, 2012). The acronym describes how volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity are the hallmarks of hypermodern society. Future leaders must make choices on an uncertain foundation and lead in an ever-changing operating space. Decisions that were successful in the past will not necessarily be successful in the future. The new challenges of the VUCA world cannot be solved by doing more of the same - what was previously the source of success (Dahl & Molly-Søholm, 2012).

To be competitive, however, the leaders of the future must be flexible, adaptable and adaptable. The ability to quickly make sense of unfamiliar contexts and capitalize on them is more important than ever. That's why learning agility is also emerging as one of the overriding qualities for leaders at all levels.

As business psychologists working with organizational and leadership development in both large and small companies, nationally and internationally, it is our experience that today's leaders are significantly challenged by the new conditions of the business world. They feel the inevitable demands of the VUCA world for speed and flexibility, but lack concrete development tools and guidelines to navigate these new challenges. One of the problems is that the development of leadership development tools has stagnated (Hogan & Warrenfeltz, 2003). The majority of models and tools available on the market date back to the 1990s and do not encapsulate the complexity of the VUCA world (Sørensen & Grøn, 2015). How will leaders be able to solve the problems of the future with yesterday's tools created for a different context? The key questions for future leaders, HR departments and consultants working to develop sustainable and effective leadership are therefore:

- What concrete tools can we use to successfully navigate a VUCA world?

- How can we transform theories and research into practical action that creates visible and measurable results for our organization?

In this article, we will try to provide a practical and research-based answer to the above questions.

Versatile management

Our take on the key questions for future leaders is based on the concept of versatility. We will try to illustrate how the ability to balance complementary leadership competencies can empower future leaders to navigate the tension between strategy and people in the complex modern workplace. We will introduce the versatile leadership model that can be used to create leadership balance at the individual level, to ensure the right leadership at the right level at the different levels of the leadership chain and to develop an overall balanced leadership chain. Our argumentation is based on the latest research by the fathers of versatility, Robert Kaplan and Rob Kaiser, whose research shows a clear and increasing correlation between versatile leadership and leadership effectiveness (Kaiser, Overfield & Kaplan, 2010).

READ MORE ABOUT OUR EDUCATION

LEAD

offers certification in the development of agile leadership with the development tool The Leader's Versatility Index (LVI)

With a certification, you will be equipped to use LVI in development processes in your organization at the individual, group and organizational level.

Mastering conflicting leadership skills

In popular leadership literature, the focus is often on how organizations create a cohesive leadership chain and develop effective leadership chains (Dahl & Molly-Søholm, 2012). In this article, however, we will turn our attention to the leader's individual leadership competencies, which are the fundamental building blocks for effective leadership chains and leadership teams. In order to create a solid foundation for effective leadership at the organizational level, it is necessary to work with the leader's individual leadership competencies (Grøn & Sørensen, in press). And here, versatility is a new and highly relevant leadership concept.

The concept of versatility was introduced by Robert Kaplan and Rob Kaiser, who define it as:

"The ability to read and respond to changing conditions and circumstances with a full management repertoire; the ability to effortlessly [1]to use opposing approaches to leadership, without being limited by personal preference for one particular leadership style and without prejudice to the opposing leadership style "

(Kaplan & Kaiser, 2003 - authors' own translation)

A versatile leader possesses a broad, contradictory leadership repertoire and is able to balance different leadership competencies according to the needs of the context. The versatile leader does not see their competencies as conflicting and incompatible, but rather as complementary and necessary to act appropriately in complex and conflicting demands (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2003). The leadership repertoire includes both a strategic and an operational focus, as well as a directive and a supportive approach to employees (Kaiser, Overfield & McGinning, 2012).

The concept of a "full leadership repertoire" may seem diffuse and intangible at first glance. To address this criticism, Kaplan and Kaiser developed the Versatile Leadership Model, which transforms theory into a practical leadership tool (Kaiser, Overfield & McGinning, 2012). The purpose of underpinning theoretical understanding with a model is to offer future leaders a simple tool to achieve effective, aligned and balanced leadership behavior.

The versatile leadership model

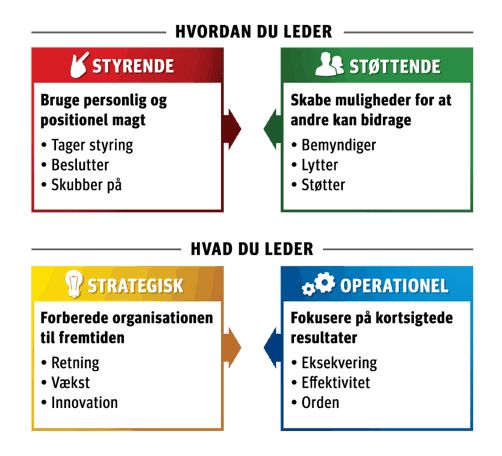

The versatile leadership model has two basic dimensions (Kaiser, Overfield & Kaplan, 2010):

- How you lead

- What you're looking for

The two dimensions consist of opposing but complementary leadership behavioral styles. (1) The How you lead dimension differentiates between directive leadership and supportive leadership. (2) The What you lead dimension differentiates between strategic leadership and operational leadership. Each of these four overall leadership styles is broken down into three additional specific behaviours to clarify which behaviours characterize this specific leadership style.

Figure 1: The versatile leadership model.

How you lead

This dimension describes how the leader can use both directive and supportive leadership. A versatile leader has both leadership styles in their leadership repertoire and can switch effortlessly between them according to the needs of the context (Sørensen & Kaiser, 2017). The leader can bring a directive approach into play by taking active control, making decisions and setting high professional standards for those around them. In other situations, the leader adopts an inclusive, supportive leadership style and gives others space to take the reins by empowering, listening and supporting. And, finally, the versatile leader can bring both into play in the same situation with a finely developed sense of how they both contribute to the successful completion of a task.

Avoid unbalanced leadership - play on all keys

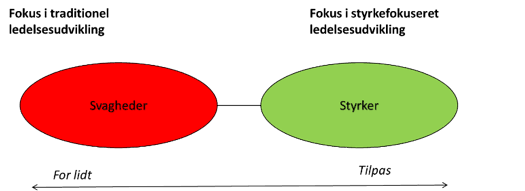

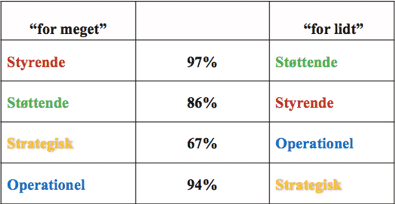

Research by Kaplan and Kaiser shows that excessive preferences for one of the two sides of the leadership dimensions limits the functioning of leaders and the organization. In a study of over 18,000 leaders globally, 91% of leaders practice unbalanced leadership and are less effective than they could be (see figure 2) (Kaiser, Overfield & Kaplan, 2010). Individual imbalances that are likely to emerge over the course of a leader's career and rise through the leadership hierarchy.

Kaplan and Kaiser found that versatility describes over half of the leadership behaviors and priorities that separate the most effective leaders from the least effective leaders (Kaiser, Overfied & Kaplan, 2010). A figure that has been steadily increasing since Kaplan and Kaiser conducted the first versatility and effectiveness measurements back in the 1980s. A finding that gives rise to the hypothesis that versatile leadership becomes more important as the speed and complexity of the work environment increases. In addition, they found that versatility is directly linked to:

- Employee engagement and job satisfaction

- Team morale, cohesion

and confidence (in strategy execution). - Team and business productivity

When 91% of leaders are in a state of leadership imbalance, significant nuances and opportunities to optimize and streamline their leadership are lost. To avoid limiting efficiency and effectiveness, we recommend that leaders continuously adjust and adapt their leadership style to the specific situation, task and level of leadership. Leadership is first and foremost a practice, and it seems that an increasingly important skill is being able to adapt your leadership practice to the ever-changing environment - while building knowledge and learning in the process.

Unbalanced leadership - four archetypes

As previously described, the four complementary leadership styles of the versatile leadership model are demonstrably necessary, and the contextually conditioned balance between them is necessary for effective leadership. However, research shows the presence of a double efficiency loss: leaders often have strong preferences for one side of the two leadership dimensions while neglecting the complementary one (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2006). As mentioned above, a study of more than 18,000 middle and top managers shows that unbalanced leadership is an extremely widespread phenomenon (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2016). In addition, 97% of leaders who scored too high on the directive leadership style were simultaneously rated as being too uns upportive - see figure 4 (Kaiser, 2016). The imbalance of too much of one thing is exacerbated by too little of the complementary.

Based on the versatile leadership model and research, four basic archetypes of unbalanced leadership can be identified: The Field General, The Hero, The Playing Coach and The Servant. Leaders' preference for leadership styles often reflects where they are in the leadership hierarchy and which transition in the leadership chain they come from (Dahl and Molly Søholm, 2012). Imbalances can also be caused by the leader overcompensating for certain leadership competencies during a leadership transition.

In the following, we will describe what characterizes the four archetypes, which archetypes are particularly prevalent, and what pitfalls and limitations arise when leaders overemphasize certain leadership competencies and neglect others.

1. the field general: The combination of managerial and operational leadership

The most common preference combination is an over-focus on managerial and operational leadership. This archetype is referred to as the "field general", as leaders with this preference combination often find themselves in the cockpit of organizations with constant pressure to perform (Sørensen & Grøn, 2015). This type of imbalance is particularly prevalent in managers who are transitioning from employee to manager of employees. They will often be at the lowest level of management and new to the role of a leader. An expectation of productive operations, efficient execution, a direct leadership style and a willingness to move forward (and upwards) can easily drive a manager towards a very controlling and operational approach to their employees. Often, we see this type of employee behavior leading to organizations promoting employees to manager. The limitation of this imbalance, however, is that the leader may appear as a dominant micromanager who is unable to include a long-term strategic view in their leadership and support their employees sufficiently. In Kaiser and Kaplan's study of leaders globally, 33% fell into this category. Many leaders are therefore at risk of being limited by a lack of strategic perspective and lack of employee support.

2. The playing coach: The combination of supportive and operational leadership

The combination of a propensity for a supportive leadership style combined with an operational leadership style is the second most common preference combination. This archetype, which we often see in Danish organizations, is referred to as the "Playing Coach", as leaders in this category often see their employees at eye level and work side-by-side with their team (Sørensen & Grøn, 2015). This type of leader is particularly common where frontline or middle managers have been promoted to lead the team they were previously part of. The manager hasn't really embraced the transition into their leadership role and therefore struggles to assert themselves to their employees, and also doesn't have an eye for the strategic aspects that need to be balanced with operations. One of the pitfalls of this archetype is letting the fear of losing popularity and belonging as a "friend" prevent the establishment of respect and authority when making difficult choices. In these situations, the playing coach will find it difficult to correct and assert his or her power in tense situations for fear of losing status as "one of the guys". 19% of the leaders in Kaplan and Kaiser's study were in this category.

3. The Hero: The combination of managerial and strategic leadership

Leaders who tend towards a directive leadership style combined with a strategic leadership style make up the "hero" archetype. This type of leader is referred to as a hero because they are often compelling, inspiring and charismatic, and at the same time, they have a big vision for their organization. This type of leader is often admired by their employees and is often found at the middle management level, where the strategic work becomes more important and is valued more than at the employee level. The challenge for this type of leader is that they move too far up in the strategic helicopter and lose interest and ability for the operational focus, thus failing to translate the big visions into concrete action. Kaplan and Kaiser's study showed that 20% of leaders fell into this category.

4. The servant: The combination of supportive and strategic leadership

The combination of a preference for a supportive leadership style combined with a strategic leadership style is the rarest imbalance. This type of leader is referred to as the 'servant', where they will often be strategically strong and use a facilitative and inclusive approach to achieve their vision. This archetype is often found at both ends of the management chain. Either the overly strategic frontline manager who has let go of their grip on operations and doesn't assert themselves as a leader. Or the hyper-strategic top manager whose visions have lost their grounding and connection to operations, who delegates a lot but doesn't empower subordinates to implement their visions, let alone hold people accountable for their responsibilities and results.

The challenge for this archetype is not being able to put strategy into practice. Often, the combination of lack of operational clarity and fear of stepping up to the plate in tense situations will lead to poor results for this type of leader. In Kaplan and Kaiser's study, 9% of leaders were in this category.

Figure 2: Distribution of preferred behavioral management styles among 18,216 middle and senior managers, LVI global norm database (2010-2016).

READ MORE ABOUT OUR EDUCATION

Want to get even better equipped to manage processes?

The Process Consultant program gives you the methods to design, facilitate and lead strategic development processes and changes to create the impact you need.

This is an education for those who work with development, processes and change management.

Overused strengths - when more is too much

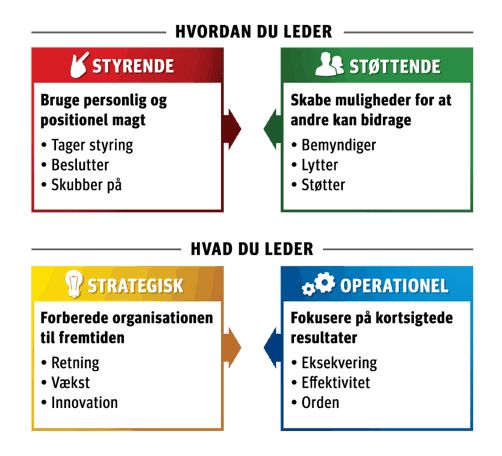

The classic simplification - strengths and weaknesses

A classic blind spot in many development tools and management theories is that they implicitly assume that more is always better - a "maximum is optimum" mindset. The problem, however, is that inefficiency is just as often caused by managers doing too much of something as too little of something (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2006; Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). Unfortunately, only a few development tools identify when something is in deficit and when it is in surplus. Nuances that the classic 0-10 scale and traditional ways of working with leadership development do not take into account.

While classic leadership development has mainly been deficiency-focused and concerned with "fixing" what was wrong with leaders, newer strengths-focused approaches have often completely ignored any deficiencies and jumped into the other ditch, believing that a focus on strengths automatically eliminates any weaknesses (Buckingham & Clifton, 2001). However, our research and practical experience shows that such one-sided approaches fail to capture the complexity of effective leadership (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013).

The one-sided deficiency or strengths-focused approaches are not sufficient if leaders are to develop complex behaviors that match the VUCA reality we find ourselves in - and promote their effectiveness. The playing field must be expanded, and the versatile leadership model does this by operating with three categories of leadership behaviors and areas of focus in leadership development: strengths, weaknesses and exaggerated strengths - see figure 3.

This triad differs from both the deficiency- and strengths-focused approaches because it accepts that overplayed strengths are just as much of a problem for leader effectiveness as weaknesses, which is supported by research (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013; Kaiser & Kaplan, 2009). This expansion of the understanding of leadership has crucial implications for how we should practice

leadership development. The versatile leadership model provides a unique starting point for developing effective leaders, as it creates a solid foundation for turning up what the leader is doing too little of(weaknesses), turning down what the leader is doing too much of (excess strengths), and continuing what the leader is currently doing just right(strengths).

Strength to surpassed strength

Strengths easily get out of hand. It comes naturally to humans to cultivate behaviors that have previously led to recognition and success (Sørensen & Kaise, 2017). Similarly, it is natural for humans to make use of behaviors that provide a sense of continuity and coherence in our personality. Finally, people tend to repeat behavioral patterns when they are in stressful situations and when they lose concentration (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2006). However, when we fall in love with our strengths and cultivate them to the extreme, we risk overlooking when a situation calls for something different and not just more of the same (Dahl & Molly-Søholm, 2012). Strengths can also be exaggerated unconsciously, for example, where a person is not aware of their own strengths and therefore does not recognize when they are exaggerated.

Overemphasized strengths are a major source of unbalanced and ineffective leadership. Imbalances typically occur when leaders identify so strongly with one aspect of their leadership that they become blind to the fact that there are other, complementary approaches that can contribute to improved leadership performance (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). Capitalizing on one's strengths is not problematic in itself, quite the contrary. However, the distortion occurs when a leader is drawn to their own strengths and therefore exaggerates them to such an extent that it has a negative effect on those around them.

Research shows that leaders are 5 times more likely to overstate their own strengths compared to other traits and behaviors (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). In line with this, as previously mentioned, 97% of leaders who are rated as overstating the use of a directive leadership style are also rated as understating the complementary supportive leadership style. This paints a picture of leadership imbalance, where too much of one behavior is reinforced by too little of the complementary behavior (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). A picture that is quite general, as can be seen in figure 4 below.

For example, an energetic operational leader may become so eager to maintain day-to-day operations that they take actions that directly reduce the chances of long-term success. Similarly, reflective strategic leaders may spend so much time thinking and planning that they fail to execute their plans and put them into action. In a versatile perspective on leadership development, it is therefore relevant for leaders to reflect on the following:

- Which behaviors reflect my personal preferences and values? What are the consequences and how does this limit me in fulfilling my leadership role?

- Which behaviors that used to be a source of success, but are no longer necessary for success, do I hold on to?

- Is there a certain unhelpful behavior and inclination that I automatically maintain when under pressure? And how can I avoid it?

- What strengths would others attribute to me? Do I unconsciously overstate these, either because it brings recognition or because it comes naturally to me?

Sources of imbalance

Kaplan and Kaiser have researched which factors in particular provoke imbalances in leaders (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). In their research, 5 key sources of imbalanced leadership emerge.

- A "The more the better" mentality

A one-sided focus on more of a behavior being inherently better drives many leaders to overdo behaviors that were originally a natural strength (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). An example of this is the overinvolving manager who is good at listening to employee frustrations. The more the employee articulates their frustration, the more the manager listens. In the desire to be a listening leader, the leader may risk overlooking the fact that the employee may be asking for the leader to set direction, take control and actively contribute with a concrete solution or make a decision (Grøn & Sørensen, in press). - A skewed mentality

Leaders' actions and behaviors are guided by subjective assumptions, values and attitudes. If these are not aligned with the needs of the organization, this distortion will be reflected in the leader's behavior. Mental distortion can lead to both too little and too much behavior (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2003). The manager will naturally de-prioritize the management work that he or she does not consider important, and at the same time, the manager will overdo the management tasks that he or she considers particularly important. However, the leader's subjective perception and priorities are not necessarily in line with the organization's wishes and priorities. - Mental miscalibration

In mental miscalibration, the leader's perception of their own behavior and leadership style is not in line with the outside world's perception of the leader. For example, a leader may perceive themselves as highly supportive without their colleagues necessarily believing the same (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). Miscalibration is often due to a lack of direct and honest feedback from the environment. - Fear of inadequacy

Fear of inadequacy and lack of leadership skills can drive leaders to isolate themselves and refrain from relationship work with employees. However, if a manager continually avoids tasks that could potentially develop their weaknesses, they will end up in a vicious cycle where their fear of inadequacy will create self-fulfilling prophecies (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013). At the same time, the fear of inadequacy can also lead to overcompensation, where the leader exaggerates their perceived weaknesses to prove their worth. For example, a manager who is unsure of their own leadership skills may end up taking up all the speaking time at meetings and appear inappropriately dominant in an attempt to appear confident (Grøn & Sørensen, in press). - Uneven competence development

If a manager has particular strengths, they may risk only being assigned tasks that utilize their strengths. This deprives the manager of the opportunity to develop their leadership repertoire. Uneven competency development can also be due to organizational factors such as a lack of management education, a massive focus on strategic management, for example, or that the manager does not have the opportunity to acquire basic management tools (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2013).

The practicalities of working with versatility

If future leaders want to develop versatility and effective leadership, they need to be presented with methods to turn theory into practice. This is where traditional skills development doesn't work. It's not enough to send the manager on a course in new methods. The transfer problem has long documented that managers do not get enough out of generic competence courses disconnected from everyday organizational life (Grøn & Molly-Søholm, 2016).

As previously described, only 9% met the criteria for versatile leadership (Sørensen & Kaiser, 2017). If you are not among the 9%, but want to be, it requires that the leader is willing to work on both their behavior - the external work, and their mindset - the internal work, which is often referred to as personal leadership (Kaiser, Overfield & Kaplan, 2010). If the leader only addresses one of the two areas of focus, the change will often be short-lived and the leader will quickly fall back into old imbalances. If we really want to develop versatile leaders equipped for the challenges and opportunities of the future, we need to work on both areas.

Conclusion and perspective

Future leaders face an important question: how can I succeed and thrive in and under the new world of leadership? In this article, we have provided our practical and research-based take on a concrete leadership tool that can help leaders develop more effective leadership in a VUCA world.

At the same time, it's important to point out that the VUCA world is not the only world out there. There are still organizations that operate on traditional terms, just as there are departments in VUCA affected organizations that are not subject to disruptive terms. Bureaucracy, law and rule-driven processes are still prevalent and still form the foundation for the security and stability of organizations.

Regardless of the organizational reality, our experience shows that the versatile leadership model can help qualify and develop the organization's leaders so that they benefit from the entire leadership repertoire.

We hope to have shown how the versatile leadership model can be used to strengthen both the individual leadership foundation and the overall leadership chain. And last but not least, we hope that the article can contribute to a more frank and nuanced discussion of what the future of leadership actually calls for.

Real development requires working with both behavior and mindset

The outer work - working with concrete behaviors

The alignment of overplayed strengths begins with the realization that you need to cut back on a certain behavior, combined with a sense of obligation to do so. The manager can use these two techniques when working with specific behaviors: (1) Getting to know the indicators of an impending reflex reaction so that the manager can break them. This can be developed through coaching, for example, where work is done to identify inappropriate habits and their triggers. (2) Establishing feedback loops in the form of others close to the manager, ensuring that the manager is warned if he or she falls back into old and unbalanced behavioral patterns (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2006). In our experience, the most effective leadership organizations practice aligned expectations, direct and frequent feedback between levels.

Inner work - working with mindset

However, working with the leader's overplayed strengths also requires the leader to become aware of the mindset associated with the unbalanced leadership behavior. The leader's mindset can keep the leader in an unfavorable narrative or keep the leader in a negative dynamic where one leadership style is preferred and superior at the expense of the opposite leadership style, which is feared or disapproved of. In this case, the leader can use two techniques: (1) Dismantling trigger points in situations where the leader is overusing their strengths. Here, the leader must work through the fears and beliefs that provoke the inappropriate reactions by recognizing or accepting that the fears that prevent the leader from using, for example, a controlling leadership style are rooted in a mindset that has categorized all controlling leadership as dictatorial and evil. This is, of course, a fallacy. Such a mindset is particularly common in trust-based organizations. (2) Focusing on your own strengths and taking ownership of them (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2006). Both development methods can be used in coaching, sparring or in collaboration with a skilled mentor who has the necessary conversational skills and psychological insights.

Briefly about working with weaknesses

One way leaders can work on their own weaknesses is by pushing themselves to perform a behavior they haven't done before for fear of failure. This could be allowing themselves to listen 30 seconds longer and ask 1-2 more questions before making a decision that affects more than just themselves. The leader can use two tactics in this regard: (1) Paying attention to the internal signals that arise when the leader refrains from certain behaviors out of fear of inadequacy or discomfort with working at the limits of their abilities. (2) Establishing a learning arena where the leader can develop their weaknesses in a safe forum. This can be done through transparency, by simply telling colleagues about your development focus and asking for help to succeed. It can also be done by establishing feedback loops where the manager's progress is systematically evaluated, for which there are several proven tools (Kaplan & Kaiser, 2006).

Working actively with weaknesses is, in the same way as working with overplayed strengths, closely linked to becoming aware of one's own mental barriers. If the manager wants to work actively with these, the manager can use two tactics: (1) To examine which beliefs, experiences, personal narratives and/or overall discourses that create the manager's trigger points and inhibitions. (2) To explore and receive feedback on their own strengths, as the recognition of strengths can release energy, confidence and courage to work with weaknesses.

Versatile management from top to bottom

It's not enough to develop versatility in individual leaders. In our surveys and development work, we often see a very differentiated perception of what good leadership is across the management chain. The versatile leadership model not only provides a nuanced view of the individual leader, but also the opportunity to spot imbalances in the overall leadership chain and leadership culture. An imbalanced leadership chain and leadership culture can have far-reaching consequences for organizations. It destroys employee wellbeing, engagement and productivity, as well as the organization's overall performance and future potential for success. Unbalanced leadership cultures that focus on some specific leadership virtues and ignore others - or that are fundamentally misaligned around the nature of directive and supportive leadership and the priority between operational and strategic leadership - are a great danger to organizations and the people in them.

The versatile leadership model can thus link individual leadership with an organizational perspective on leadership that ensures a common leadership foundation and the right leadership at the right level (Dahl & Molly-Søholm, 2012).

An unbalanced management chain

Different dosages of the four leadership styles are needed depending on where the leader is in the leadership chain. Therefore, imbalances will also appear in different forms depending on where the leader is in the chain. Versatility is thus relevant for leaders regardless of management level and can have a significant impact on the success of leaders in transitions from one management level to another. A commonly seen problem is when imbalances developed at one level of the management hierarchy follow the individual leader on the journey up the management hierarchy (Lombardo & Eichingers, 1999).

Often, there will be a particularly pronounced need for executive and operational leadership at the frontline level to ensure the organization's operations and execution. It's not a popular message, but Lombardo & Eichinger's research suggests that the ability to push, make quick decisions and hold employees accountable for their deliverables is essential to success as a leader of people. As managers move up the hierarchy, the need for supportive and strategic leadership will grow, and the pitfall for many managers is to maintain the behaviors that were previously necessary instead of adapting to the new demands. If the leader carries this imbalance up through the system as they are promoted, they will find that the higher up the hierarchy they move, the more misplaced and ineffective the imbalance will become. Controlling and operational leadership is perceived as self-promotion and micromanagement higher up the management hierarchy, as cross-functional strategic work with a focus on supporting subordinate managers to succeed become key value-creating attributes. The versatile leadership model can help leaders find the balance that suits their particular level of leadership.

An unbalanced management culture

A decidedly unbalanced leadership culture can also arise in the management chain, which typically happens when too much emphasis is placed on a certain type of leadership that is idealized and elevated at the expense of other perspectives. A skewed leadership culture is often closely linked to top management's behavior and perception of what good leadership is, as well as the culture and industry of the organization. Is it a sales culture with too little focus on the strategic long-term perspective and supportive leadership or a socially sustainable entrepreneurial company that overfocuses on the strategic and supportive, but fails to get off the ground and create concrete results. The reasons for organizations' unbalanced leadership cultures often lie in what top management does and admires, the organization's culture and values, and the industry and market the organization operates in.

It is therefore crucial that the entire management chain in communities reflect on:

- Are we idealizing a certain type of leadership and does this mean we are overlooking part of the overall leadership task?

- Are there any particular imbalances at the different levels of management that we're missing?

- What are the consequences of any imbalances we have identified and how can we work to eliminate them?

Conclusion and perspective

Future leaders face an important question: how can I succeed and thrive in and under the new world of leadership? In this article, we have provided our practical and research-based take on a concrete leadership tool that can help leaders develop more effective leadership in a VUCA world.

At the same time, it's important to point out that the VUCA world is not the only world out there. There are still organizations that operate on traditional terms, just as there are departments in VUCA affected organizations that are not subject to disruptive terms. Bureaucracy, law and rule-driven processes are still prevalent and still form the foundation for the security and stability of organizations.

Regardless of the organizational reality, our experience shows that the versatile leadership model can help qualify and develop the organization's leaders so that they benefit from the entire leadership repertoire.

We hope to have shown how the versatile leadership model can be used to strengthen both the individual leadership foundation and the overall leadership chain. And last but not least, we hope that the article can contribute to a more frank and nuanced discussion of what the future of leadership actually calls for.

Literature

- Buckingham, M. & Clifton, D. (2001), Now discover your strenghts

- Dahl, K. & Molly-Søholm, T. (2012),"Leadership Pipeline in the public sector", DPF

- Grøn, R.T. & Sørensen, N.H. (in press) Versatile leadership - building the individual leadership foundation at all levels, In Den offentlige Leadership Pipeline 2.0 - ledelseskraft til en ny tid, Dansk Psykologisk Forlag

- Grøn, R.T. & Molly-Søholm, T. (2016) Business-driven leadership development, Danish HR

- Hogan, R., & Warrenfeltz, R. (2003). Educating the modern manager. Academy of Management Learning and Education

- Kaiser, R. B. (2016, June). Developing Versatile Leaders for Complex Times. Keynote speech for Hudson Lounge Power Talk series, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Kaiser, R. B., & Kaplan, R. E. (2009). When strengths run amok. In R. B. Kaiser (Ed.), The Perils of Accentuating the Positives (pp. 57-76). Tulsa, OK: Hogan Press.

- Kaiser, R. Overfield, D. V. & Kaplan, R. (2010) LVI v3.0 Facilitator's Guide

- Kaiser, R.B., McGinnis, J. L., & Overfield, D.V. (2012), The How and What of leadership

- Kaplan, R. & Kaiser, R. (2006) The Versatile Leader (Pfeifer/Wiley)

- Kaplan, R. & Kasier, R. (2013) Fear Your Strengths What You Are Best at Could Be Your Biggest Problem

- Kaplan, R., & Kaiser, R. (2003). Developing versatile leadership. MIT Sloan Management Review

- Kaplan, R., & Kaiser, R. (2003). Rethinking a classic distinction in leadership: Implications for the assessment and development of executives. Consulting Psychology Journal: Research and Practice, 55, 15-25.

- Kingsinger, P. & Walch, K. (2012). Living and leading in a VUCA world. Thunderbird University.

- Lombardo, M. M. &, Eichinger, R. W. (1999). Preventing derailment: What to do before it's too late. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

- Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review,

- Stacey, R. D. (2012). Tools and techniques of leadership and management: Meeting the challenge of complexity. Oxon: Routledge.

- Sørensen, N.H. & Grøn, R.T. (2015) Versatile leadership - how leaders achieve effect in a VUCA world, Børsen ledelse

- Sørensen, N.H. & Kaiser, R. (2017),"Leading oneself in a VUCA world - part 1", Børsen

- Sørensen, N.H. & Kaiser, R. (2017),"Leading oneself in a VUCA world - part 2", Børsen

- Sørensen, N.H. & Kaiser, R. (2017), "VUCA world - are you equipped to lead in today's disruptive conditions?", Børsen

[1] Translated from English "Freely"