We find the field we are passionate about characterized by two things. An enormous amount of creativity in the many different camps populated by process consultants. The appreciative, narrative, systemic and management consultants are constantly developing new and exciting ideas and tools. An ever-increasing demand for internal and external consultant training courses, where participants are provided with concrete methods and theories that can be helpful for those who want to contribute constructively to organizational change. Both trends accelerate the need to develop a more refined language to express what good consulting practice is all about. If we look beyond the field, there are many different languages spoken in the different camps that lie in a conceptual jungle. Across these different camps, however, one thing seems to be common: each camp insists on having found the philosopher's stone. Often to such an extent that the theory sometimes becomes an end in itself rather than a tool. In this game, the customer loses.

Lewin says there is nothing as practical as a good theory. We share the enthusiasm for seeing theory and practice as closely related and not separate entities. At the same time, however, it is our experience that many theories are often not as practical as they seem. Process consulting theories often set normative rules and principles that state what the consultant should and should not do. In our experience, such rules in practice often lead the consultant into a dead end if they don't actually move the conversations forward. But what kind of theory is helpful in practice?

Barnett Pearce (2001) writes that "if we are to make our social worlds better, we should applaud any efforts that increase our collective virtuosity... We suggest that virtuosos in any field of practice (1) have a "grand passion" of their work; (2) are able to make insightful distinctions among the events and objects within the field (including seeing things that are invisible to the untrained eye); and (3) are able to engage in skilled performances."

The article continues in the next section.

Get a copy of the book "Den professionelle proceskonsulent" by Kristian Dahl and Andreas G. Juhl. Juhl.

LEAD's book skim is nonfiction for those who want to know more but don't have the time. The concentrated summaries allow you to quickly gain basic knowledge on current topics - knowledge you can use both in your management practice and as a starting point for training.

In this book, Kristian Dahl and Andreas Granhof Juhl provide methods on how to create constructive development in organizations in theory and practice. The book is equipped with a wide range of methods, which are illustrated through cases and examples . Thefocus is on team development, conflict resolution, promoting job satisfaction and many other methods. The book is aimed at the consultant or manager who is looking for effective organizational development and tools for effective change processes.

We agree with this assertion, and in this article we will focus on the idea that what characterizes the professional process consultant is the ability to make informed choices between different ways of working with the organization. Since we believe, like Gregory Bateson, that "one can only recognize difference [...] if there are two wholes [...] which have a difference built into their mutual relationship" (Bateson, 1979, p. 61--62), this ability to make choices is based on an ability to distinguish between different ways of working and competently make choices between them in concrete situations and processes with organizations.

Rather than creating yet another theory, the purpose of this article is to unfold a field in which the con-- sultant can move in order to make these decisions competently. We will call this field a consultative space. The purpose of the consultative space is thus to help ourselves and others to change the way we observe in practical situations with organizations, not to define what the consultant should or should not do in a given situation.

The consultative space

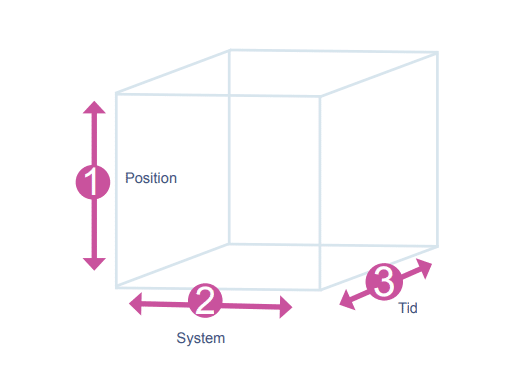

Our idea of unfolding a consultative space is inspired by Mads Hermansen's work on establishing a pedagogical universe (1998). But whereas Hermansen's universe seems abstract to us, our endeavor is to unfold a practical consultative space that builds on useful distinctions to understand how the consultant's practice plays out between actors over time. We will construct a three-- dimensional space to show this.

- The first dimension relates to the consultant's position, i.e. the basic understandings from which the consultant understands themselves and their work.

- The second dimension relates to the boundaries of the system being worked with.

- The third dimension relates to the time aspect of the work.

These three dimensions can be illustrated as:

In the following, we unfold the three dimensions - and explore some of the practical implications for consultation. In this article, we focus on the first dimension: Choosing a position. The other two dimensions are described in more detail in the book Professional Process Consulting.

First dimension: The consultant's position

In the following, we unfold the three dimensions - and explore some of the practical implications for consultation. In this article, we focus on the first dimension: Choosing a position. The other two dimensions are described in more detail in the book Professional Process Consulting.

An investment company has been through a turbulent period, struggling to navigate a drastically changing market. The leadership team has been deeply divided on strategy, but after the company was acquired by an investor, the strategy is now set. With this in mind, the leadership team approached us for assistance in restoring collaboration within the leadership team. In the team's own words, it has been badly damaged during the turbulent period. A seminar is planned with the goal of creating common ground and restoring cooperation in the team.

The exciting question now is how the consultant should structure and plan the seminar to ensure this outcome. If we break free from a rigid anchoring in a single paradigm, a wealth of exciting possibilities emerge:

The consultant can bring a strategic perspective to the task. Here, the following work questions can set the agenda:

- Who will perform which functions in the leadership team to ensure the new strategy is implemented? Who has which responsibilities? How are your efforts best coordinated within the team as well as with the rest of the organization?

Another classic approach could be to work inspired by the classic American OD tradition. Here, the underlying goal is to create learning and focus on developing the organization by allowing people to develop. The consultant looking at the situation through this lens would have the following work questions:

The consultant could also look at the situation through a systemic perspective. The interesting thing here is the importance of the context as well as the patterns in which the interaction takes place. The systemic consultant will therefore design a seminar based on the following considerations:

- What actions on your part made the previous, unclear strategy meaningful? How is the organizational and strategic context now? What actions does this situation call for from you?

Another possible lens could be the appreciative position. Here, the focus is fundamentally on creating processes that focus on best practices and dreams for the future. The consultant who sees the situation through this lens will structure the seminar program around the following questions:

- When does team collaboration work? What future do you dream of creating for the leadership team? How can you use what works to make the future you dream of a reality? What are the first steps that can be taken?

Other possibilities arise if the consultant takes a narrative position. Here, the starting point is a basic assumption that reality is created in the stories we tell. The key is therefore to make room for stories that bring the team into the position they prefer. Based on this, the following working questions could be interesting:

- What stories do you tell about the leadership team and the collaboration within it? What makes these stories possible - and impossible? What other stories could be told? What can you do to make these stories possible?

Finally, you could work from the solution-focused position. The basic assumption "the problem is not the problem, but the attempted solution" will give rise to the following working questions:

- When does your teamwork work after all? What's the smallest thing you could do more of? Who does what? When to do it?

The above perspectives are of course not an exhaustive list, but rather an illustration of which perspectives we find most helpful in consultative work.

The key is the wealth of options that arise for the consultant who is able to navigate between different perspectives. This basic understanding connects to Dewey's and pragmatism's instrumentalism: The consultant's theories are instruments that the consultant does something with. Theories are never passive and neutral descriptions. We endorse Einstein's claim that "it is the theory which decides what we can observe". Our cognition is less an expression of a precise and objective understanding of the world, but rather an expression of the lens through which we observe the world. Applied to consultative practice, this means that the consultant who wants to be able to see and do different things must be able to switch between different lenses. In other words, if we want to observe differently, we must be able to choose a different theory. As long as we maintain the same theory in our work, we will use the same types of observations and reproduce experiences. As in the introduction to this article, it is therefore our claim that the professional consultant can:

A. Distinguish between different types of theories: A prerequisite for this is that the consultant can see the difference between positions and understand that each position makes some actions possible and others impossible.

B. Make informed choices between these positions in practical situations: When the consultant changes position, the consultant's way of observing and listening changes, which means that the consultant starts to hear and see different things. This helps the consultant to say and do other things, which in turn allows the system to respond differently, which in turn gives the consultant new types of observations etc. It is therefore crucial that the consultant continuously makes reflective choices about which position is most beneficial going forward.

We see the above as a crucial practical skill that helps the consultant to change the type of action together with the organization. In doing so, we aim for a consultative practice that is emergent over time rather than stable and unchanging. What is stable is never the concrete position, but the ability to change position. It is this ability to change position that is often a prerequisite for keeping the process moving. We see this as a movement away from a theoretical normativity (the consultant should and should not do such and such in the given situation), to focus on the usefulness of the position the consultant takes with the organization. In other words, the professional process consultant can work multi-paradigmatically and pragmatically reflexive.

The multi-paradigmatic means that the consultant takes a basic position that is not anchored in a single paradigm, but rather in a reflexivity of the different paradigms or theories. This means that the consultant must consistently work with a dual perspective:

i) What do I see now based on the paradigm through which I observe the organization?

ii) What else could I see if I observed the organization through a different paradigm?

Alongside this, the consultant takes a pragmatic, reflexive approach to the current situation and chooses between the different perspectives based on the consideration: what works best here?

There are, of course, many different lenses, understood as theoretical perspectives, through which the consultant can view themselves and their consultative work. Each lens makes something clear and something unclear. Each lens makes some actions in the interaction between consultant and organization possible -- and makes others impossible. Below we describe some of the lenses we personally find most helpful to switch between1. We use concrete descriptions from practice as illustrations.

The OD position: OD2 became widely known as a particular approach to organizational development in the mid-1970s, but the main starting point for the movement is earlier. Here, three lenses are central to understanding the optics that make up the basic view of the OD tradition:

- The action research of Kurt Lewin

- The humanistic psychology especially inspired by Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers

- Human Relations school: Management and organizational theory especially inspired by Bennis, Benne & Chin and Douglas McGregor

Edgar Schein, with the OD movement, is known as the father of the concept of process consulting. A central assumption of this position is that the best way to develop organizations is to create growth for the people in the organization by providing the best possible space to unfold and contribute. The consultant does this by a) focusing on building the client's ability to understand the current situation and b) constructively intervening with the goal that the client can develop their own organization.

Case: From course to action

A municipality is in the process of establishing a new structure in the daycare sector. This means that several of the institutions are being merged. In this context, the administration has invited us to create a two-day course in change management for the affected managers. Despite thorough preparation and pre-meetings with the administration as well as representatives from the daycare center managers, the course gets off to a different start than expected. One of the participating managers breaks down in tears and says she feels paralyzed and stressed due to the fact that her staff are strongly opposed to the merger. She receives a lot of feedback from the other managers who are also feeling pressured for the same reason. After checking in with the participants, we scrap the planned program and proceed with the following process. First, we ask the leaders to consider the following questions:

What are the most important questions we need to answer together, right now, in order for you to get through the merger process successfully?

Managers are instructed to write down questions on post-it notes (e.g. What should I do when one of my employees threatens to quit because of the merger? How can I motivate my staff for a merger that I don't believe in?) We then get a common overview by having the managers stick the post it notes on a wall and sort them by theme. For the rest of the two days, we work together to find answers to the questions. In practice, this is done by managers choosing a question (e.g. What should I do when one of my employees threatens to resign due to the merger?) The managers are then divided into smaller groups and tasked with coming up with specific, practical answers to the question. We consultants also work to find answers in the form of inspiring theory and concrete tools. Once the groups have presented their answers and we have answered the question, we move on to the next question: (e.g. How can I motivate my staff for a merger that I don't believe in?) This is how we work over two days.

The systemic position: The systemic perspective is well known and often associated with the ideas of Gregory Bateson and Humberto Maturana in particular. A central assumption of this position is that you can't say anything meaningful without details about the context. Thus, the goal will always be to clarify or change the context to make other actions possible. An important tool for the systemic position is to produce circular rather than linear descriptions.

Case: The stuck pattern

The consultant was called in due to an increasingly poor collaboration between manager and employees. The manager describes the situation as follows: The employees are not doing anything, so I as a manager have to take the initiative. On the other hand, employees describe the situation as: We don't want to do anything, because our manager wants to decide anyway. The common thread in the stories is clear. Both parties see their actions from a linear causal interpretation framework. I do what I do because my employees do what they do. We do what we do because the manager does what he does. In principle, the consultant is not interested in who is right. By definition, both parties act correctly based on their own understanding of the situation. Instead, the consultant focuses on promoting a more circular understanding, which is based on what Bateson calls the "double description".

Specifically, this is done through reflective questions that help the parties to see the situation from perspectives other than their own. Inspired by Karl Tomm's question typology, we work with the following questions: If you (the employees) put yourself in the manager's shoes, what good reasons do you see for acting the way he does? If you (the manager) were to describe the situation from the employees' perspective, what would you emphasize? Through working with these questions, it becomes clear to the parties that they have basically locked each other into a destructive pattern: the employees don't take the initiative, which makes the manager make the decision, which makes the employees not take the initiative, which... Based on this realization, further work is done to create a concrete plan for further collaboration.

The solution-oriented position: With the solution-oriented position, we draw on the work of Steven De Shazer and Paul Watzlawick. The position can be summarized in the following point: all people encounter difficulties all the time. Generally, difficulties are dealt with as a routine part of daily life. In some cases, the attempt to deal with the difficulty fails. If this happens repeatedly and people have no better alternative solutions, the problem arises. The consequence for the consultant with this approach is clear: since the problem is a result of persistently applying the wrong solutions, the consultant's main role is to help the customer find and apply a different, more effective solution. Or in the words of Steve de Shazer: "the problem is not the problem, but the solution attempted."

Case: Beyond the ramp

A team of salespeople wanted help to get "off the ramp" with their sales work. They highlight that the team has fallen into a negative spiral where they have lost faith in themselves and are unable to kick down the door to new customers. With this in mind, the consultant creates an action learning program for the group. The first workshop is based on solution-oriented principles. Initially, work is done on finding exceptions. That is, situations where the problem should have been present but wasn't. This is based on the following working questions: When is the problem not present? When is the problem present to a lesser degree than usual? When was the reaction to the problem different than usual? Through working with these questions, salespeople find a number of situations where they were able to kick down the door with new customers despite their own expectations. This provides many new insights and the mood of the group changes significantly. The consultant then focuses on clarifying the exception through a series of probing questions: How is it different when the problem is not present? What makes the problem not present? What do you do there that you don't normally do? What do you/others notice? By working with these questions, it becomes very clear which sales methods work and which don't. Salespeople spontaneously create a little handbook - and now feel clearly equipped to give sales a run for their money. To reinforce this positive movement, the consultant concludes by focusing on using the exception to find ways forward. This is done through joint reflection on the following questions: What can we learn from the exceptions about how to combat the problem? How can we create more exceptions? What paths do the exceptions suggest we should take?

The appreciative position: "We can't ignore problems - we just need to approach them from the other side" (Cooperrider & Whit-- ney, 1999, p. 8). With the appreciative stance, we draw on the work of Peter Lang, David Cooperrider and Marcus Buckingham. A central assumption of this position is that development is promoted by examining strengths, positive intentions, best practices and how these can be connected to dreams and ambitions for the future. This as an alternative to working on developing organizations by improving weaknesses or examining problems.

Case: The saving

A management team is about to implement a multi-million dollar cost-cutting program. The management team is very concerned that the upcoming process will exacerbate an already tense relationship between managers and employees in the organization. With this in mind, a consultant is hired with the goal of helping the management team navigate this situation. The first step for the consultant is to work with the management team to shift the focus from the problems of the past to hope for the future. Specifically, this is done by working with the question: What do you hope employees will say after the process about your way of handling the process as managers?

The idea behind this question is that the answers help the leadership team articulate what they want to achieve. Therefore, the question is angled to be forward-looking, relational (taking the employee's perspective on them as leaders) and appreciative (asking for hope rather than worst-case scenarios). The management team spends some time discussing this question and comes to the conclusion that they hope that employees will say that they had completed the process "properly". This becomes

starting point for further coaching with the management team. Here are some of the important working questions:

- What does it mean that you implement the process in such a way that employees will say that you have done it properly? How can you use these perspectives to actually implement the current savings?

The narrative position: The narrative position draws on the work of Michel Foucault and Michael White. A central assumption of this position is that language and stories exert a power, in the sense of a creative force, on the actors in the organization. Development is thus created by examining what stories are told, what these stories make possible and impossible, and what alternative stories can be told.

Case: Narrative pre-meeting

A management team wants to gain new perspectives on their own situation. It has been characterized by great disagreement within the group. Therefore, a development process is arranged to strengthen the collaboration in the group. Here is a brief description of how the consultant acts in the pre-meeting from the narrative position.

Initially, the stage is set by clearly labeling the problem as something that is outside the customer. The goal is: a) to create an alliance between the consultant and the customer facing the problem, and b) to lay the groundwork for the customer to wriggle free from an internalized problem discourse. This is done through an externalizing dialogue. E.g. Consultant: If you had to name the problem, what would be appropriate? Manager: I don't know I guess you could just say that we've been hit by collaboration problems. Consultant: Then we can try to see how you can get a handle on the collaboration problems...

Now that the problem has been named, the focus turns to examining the impact of the problem. It's important to note that the goal is not to objectively identify the problem in a modernist sense. Instead, the goal is to acknowledge the situation the customer is experiencing. Here, the consultant continues the dialog based on the following questions: What effect have the collaboration difficulties had on the relationship with customers? How has the collaboration difficulties affected your relationship with employees? How has the collaboration difficulties affected the way you see yourselves as a management team?

With this in mind, as well as to reinforce externalization, the focus is now on creating a process in which the customer evaluates the impact of the problem. The goal is to hold the problem at arm's length, after which the consultant and customer look at how the impact of the problem harmonizes with the customer's goals:

How do you feel about the impact of Collaboration Difficulties? Is there anything you would like more or less of? Will this be a positive or negative development?

Descriptions of problems can only exist if there is also a wish that things were different. Derrida refers to this phenomenon as the absent but implicit. If we return to the story of the collaboration difficulties, the consultant articulates the absent but implicit in the following way: What makes you think the way you do about the impact of the problem? What values, desires and hopes that are important to you are impacted by the problem? What is it that you dream of that the problem stands in the way of?

The strategic position: With the strategic position, we draw on change management and classic as well as modern strategic thinking. This is obviously a gross contraction, but what we are interested in is the wealth of tools that can help organizations connect goals and means in effective business processes. A central assumption of the strategic position is that the consultant must continuously help the organization clarify and develop the organization's strategic goals and then clarify how the organization's resources are prioritized and brought into play to achieve these goals.

Case: An advertising agency

An advertising agency has a new strategy, but finds that in practice the organization acts as if nothing has happened. The management team therefore invites us to facilitate a series of seminars. The goal is to challenge the management team and play devil's advocate, with the intention that the management team will take a closer look at the organizational structures and the connection to the strategy. In practice, we structure the seminars as an action-learning process. This means that between seminars, managers translate the conclusions into action, which is followed up on at the next seminar. Here is an example of some of the questions that were worked on at two of the seminars:

Inspired by Porter's strategic thinking, we focus on the value chain. To do this, we use the following working questions: What are the most important functions that need to be performed in order for the strategy to be executed? Who in the management team "owns" which functions? How is coordination between the different functions ensured? Working with these questions makes it clear that you have established the functions (e.g. sales organization, CRM, etc.) that will make up the value chain. However, it is extremely unclear who in the leadership team owns which functions. The consequence of this is that, in reality, it is extremely difficult to manage the organization. The leadership team is therefore continuing to work on creating a clear and consistent management structure.

In the following seminar, we will focus on the reward structure based on the following questions: What are the most important goals you as a management team need to achieve in order to execute the new strategy? Overall? And each individual manager? What KPIs (key performance indicators) do each of you have now? How do they relate to the goals? Through this work, it turns out that what managers are measured on - and rewarded for through performance pay - is more aligned with the old strategy than the new one. Based on this, the management team draws up a proposal for new KPIs, which they will work to implement after the seminar. A working group is also set up to review the employee reward structure.

In perspective, the most important basic skill is being able to distinguish and choose between a number of positions. These are the basic understandings that the consultant uses to understand themselves and their work. The positions that the consultant is aware of thus constitute the first dimension in the consultative space. The goal is not to establish a number of exhaustive categories for consultancy practice, but instead to work on highlighting distinctions that can help the consultant to move themselves and their way of working in practice.

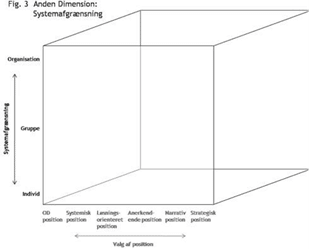

Second dimension: System

Two daycare centers are in the middle of a merger process. One is approximately twice the size of the other. The manager from the "big" institution is to step in as the new manager. The manager from the smaller institution will be the deputy manager. The consultant is contacted by the new manager, who is concerned that the manager (current deputy manager) and the employees from the smaller unit perceive the merger as a crucial loss. The consultant is asked to meet with the employees and help them through the process. The consultant challenges the client on this request. It turns out that the manager has not yet made any targeted efforts to help employees find a common culture - and say goodbye to the old organizational structure. With this in mind, the initial agreement is that the consultant will coach the manager on how to do this in practice. Over the next month, the manager and consultant meet for four coaching sessions, and between these, the manager works intensively to put the insights into practice. As a result, the manager feels that the employees have moved on. The manager now sees the next step as getting the management team to function more optimally. In addition to the manager and deputy manager, this consists of two department heads. The parties come together in a pre-meeting and all agree that a group coaching session would be helpful. The goal is to clarify roles and responsibilities and provide inspiration on how to tackle various challenges related to the merger. Two months and a series of group coaching sessions later, the leadership team is now truly functioning and acting as the team they want to be.

The new structure is now largely falling into place thanks to the efforts of the managers themselves. This is confirmed by the fact that employee representatives are calling for a joint seminar for the entire institution. The goal of this seminar is to help the entire institution go from "1st division to champions league". After a pre-meeting, a joint event is planned for all managers and employees. Inspired by Open Space Technology, the theme is: What questions do we need to find answers to in order to go from 1st division to champions league?

Everyone starts by formulating the questions that they each consider most important. For example, how do we establish a good working relationship with the parent board? How can we work well with bilingual children? How can we document our efforts in a good way? Subsequently, working groups are formed around the formulated questions. The job of the working groups is now to find concrete answers to the question they are working on. The seminar ends with the groups presenting a) the questions they worked on, b) the answers they have found. After the seminar, the groups continue to work on implementing their answers in everyday life.

A common feature of the case above is that the following questions need to be addressed several times throughout the process: Who should talk to whom about what and how in this organization to create positive development? Initially, the consultant works in a person-to-person relationship where the manager is coached by the consultant. Next, we work with the management team and finally the entire organization. Each choice involves an opt-in as well as an opt-out of who should talk to whom about what. In each of these choices, the system that the consultant works with is created. Or in the words of Bateson (1972): "Every system is created by the making of a boundary". It is our assertion that the consultant, in collaboration with the client, always delineates the boundaries of what is being worked with. Therefore, system delineation is the second dimension in the consultative space.

The very act of delineating the system, meaning the answer to who should talk to whom about what, is an ongoing and intervening event that the consultant must be in dialog with the customer about. Often the answer to this question will change during the consultation process itself, and advantageously so. In practice, this will have a significant impact on the consultant's way of working. In the second dimension of the consultative space, we work with the following distinctions:

i) Person: i.e. one-to-one conversations, which could be a coaching conversation, an initial pre-meeting with a manager or an interview for an organizational survey.

ii) Group: these groups can be both existing groups in the organization, e.g. a team that the consultant will help with team development, or a group put together for a specific purpose, e.g. a project group that will carry out a major change task in the organization.

iii) Organization: examples of this could be the theme day, where the entire organization comes together to develop shared values, or the Open Space conference, where common answers to strategically important questions must be found. In large organizations, it is often unrealistic to work with the entire organization at the same time. In this situation, you need to work through steering groups, project owners, etc.

Each of these distinctions calls for specific working methods that the professional process consultant must master:

a) In the meeting with the individual, it is crucial that the consultant masters coaching skills.

b) When working with groups, coaching, decision-making and planning methods that match the size of the group being worked with are crucial. As is the consultant's ability to lead the process towards a common goal.

c) When working with the organization as a boundary, the most important thing is of course that the consultant masters methods that can involve the entire system. Open Space Technology, world cafe etc. are examples of how this can be done.

The dilemma in system scoping will always be that there is:

- actors who will have influence and interest in what happens, but who will not be present.

- Topics and ways of working that are left out so that others can get attention.

- often different systems at different points in the process, but the process should feel meaningful and cohesive.

It's important to note that a delimitation of the system does not necessarily mean a delimitation of the effect on other systems. Even though the consultant in the example above is working with the management team, the purpose of the work is an intervention in a larger system. This also means that another form of system boundary is the one that the actors make linguistically when using markers such as "I", "you", "we", "the team", "the other teams", "the organization", etc. So in practice, there will always be two system boundaries: the actors that are present and the actors that are linguistically focused on and thus not focused on. The practical value of this dimension is that although the consultant's position may be the same regardless of how we delimit the system, the system delimitation itself will involve bringing different consultant practices and methods into play. With this in mind, the consultative space looks like this:

Third dimension: Time

Case: You are a consultant implementing a project that introduces appreciative theory and working methods with the goal of promoting collaboration and job satisfaction. The first day of the kick-off seminar has barely begun when an employee stands up and crosses his arms and says: "Everything you're saying about being appreciative is great, but we're really frustrated!

What does the consultant do now? The challenge is threefold:

1. in the moment, the consultant must master responding in a way that makes sense to the employee who has stood up.

2. At the same time, the consultant must act in a way that makes sense in light of the program set for the day's work as well as the time in the day's program.

3. Finally, the consultant must act in a way that makes sense in relation to the project's ultimate goal of promoting job satisfaction through appreciative work methods.

The story illustrates what we see as the third dimension in the consultative space: time. The consultant must be able to handle the above three time perspectives simultaneously and ensure congruence between them. Let's imagine that in the example above, the consultant gave the following response to the frustrated employee: It's not the goal of today to talk about your frustration. We're here to talk about what's working. This response in the moment would clash heavily with two other time perspectives. Firstly, it would be difficult to credibly implement the event, i.e. today's program to teach appreciative methods. After all, the participants will have seen that the consultant has not mastered being appreciative of perspectives other than his own. Furthermore, the consultant's response would clash with the process as a whole, as the consultant's behavior institutes norms for a form of interaction that is anything but appreciative. In other words, if the consultant doesn't master working with three time perspectives simultaneously, things fall apart.

Our definition of time as the third dimension of the consultative space is based on the simple fact that every practice takes place over time. Barnett Pearce (1999) argues that when we meaningfully make a beginning and an end in time, we have created an episode. But this episode can be very short (two seconds - something crucial happened here) or very long (two years - the merger process began and ended here). Both can be meaningfully called an episode, even though they have very different temporal extents. Distinctions in time are not objective, but social constructs. The interesting question is therefore: Which temporal distinctions do we need if we want to create meaningful development processes? We find the following distinctions helpful:

1. The moment: these situations can be briefly described as where the customer does something - the consultant does something - the customer does something. The process consulting approach is often criticized for focusing primarily on this, which we don't see as the case. However, it offers a wide range of useful methodological approaches for navigating the "here and now". We unfold these in the book Professional Process Consulting. In short, the two most important questions that the consultant must permanently address in the here and now are

a. How can I act meaningfully towards the customer right now?

b. How does it relate to what has happened and may happen? (how does it relate to the event and the course of events - points 2 and 3)

2. The event: by events we understand that which, within a defined time frame, extends beyond the moment. Examples of an event are:

- a strategy seminar that is part of a long-term organizational development process.

- a teaching module that is part of a management training program.

- a follow-up meeting in a conflict resolution process.

The common feature of the above is that they a) have a fixed program, b) are part of a longer process, and c) are an element that will contribute to achieving a given goal in a longer process. It is our contention that in order to succeed in practice, the consultant must be able to distinguish and choose between a number of methods and tools when working with the event. Good working questions to choose from are here:

- What activities and processes can I use to achieve the desired purpose of the event? How do I ensure that this event meaningfully supports the overall goal of the process? How does the event connect with the actors' experiences and events prior to the event and the events the actors can create in the future? In practice, you will often structure the event using some of the many methods provided by the different positions in the first dimension.

3. The journey: we define the journey as the total series of meaningful moments and events within the framework contracted by the consultant and the client. Examples of trajectories are:

- an organizational development course

- an internal leadership training

- a conflict resolution program.

Processes always involve an alternation between time with the organization and consultant - time apart - time together, etc. This kind of process can in turn give rise to very different types of consulting practice. If the consultant works from a phase thinking of:

i) Analysis of the organization

ii) Establishing objectives for the change project

iii) Action planner

iv) Implementation

v) Evaluation and adjustment

Or does the consultant work from action learning and participation principles? Or both? The key is for the consultant to master a number of methods for designing courses. It is beyond the scope of this article to go into these in depth, but working questions that can guide this choice are:

- What goal should the process achieve? What events should the process consist of to ensure this? What activities should take place between events? How do you tie it all together?

With this in mind, we introduce time as the third dimension in the consultative space.